What are the distinguishing features of a fertile soil? How can fertility be maintained and increased? Three Agroscope research groups are taking a close look at soils and developing productive farming methods that encourage soil fertility.

Vegetables, fruits, cereals, meat, potable water – 95% of our foods come from the soil. Soil is a vital resource not just for agriculture, however, but for our whole planet: it supplies plants with a reservoir of nutrients, provides a habitat for one-quarter of all living species (biodiversity), contributes to the functioning of ecosystems inter alia with the carbon, nitrogen and water cycle, acts as a water filter and reservoir, and sequesters large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere (greenhouse gas).

In a country like Switzerland, soils suitable for agricultural use are a very scarce resource.

It is therefore important that the agricultural sector and society alike know how soils function and what promotes their fertility.

This is precisely the aim that Agroscope has in mind, particularly with its research in the form of long-term trials on arable-crop plots on its Changins and Reckenholz sites, as well as with innovative approaches focusing primarily on the soil microbiome.

Organic carbon – the key to fertility

A 2018 general survey of the trials carried out by Agroscope over a 50-year period showed that substantial amounts of organic carbon can be added to the soil over the long term through farmyard manures and residues of cultivated crops. This parameter plays a key role in soil fertility and in the sequestering of carbon dioxide. However, only a consistent supply of manure can maintain the soil’s organic carbon content, and thus increase crop yields. The impact of the different kinds of tillage – plough, reduced tillage, no-till – on soil fertility shows that all methods result in a decrease in organic-carbon content. Reduced tillage can slow down this effect, however. All three sorts of tillage lead to similar yields over the long term. Crop rotation brings no advantages in terms of the soil’s organic carbon content, but it enables higher yields to be achieved both over the short and long term. To summarise, a combination of regular inputs of organic manures, reduced tillage and a varied crop rotation can maintain soil fertility and field-crop yields over the long term.

How can compacted soils regenerate?

Around one-third of all Swiss soils are affected by compaction. Increasingly heavy machinery on waterlogged soils causes compression of the soil and damage to soil structure. This negatively affects air and water permeability, and hence the development of roots and soil organisms. By assessing the risk before driving heavy agricultural machinery over soils, compaction can be avoided. But what can be done if a soil is already compacted? Research work on this subject is testing which farming methods have a potential for improvement. Tillage alone will not succeed in restoring soil structure. A sensible approach consists of a crop rotation with deep-rooted plants and application of an organic manure that nourishes the soil organisms and promotes the natural soil processes. These measures are also important for an optimal humus content, which is in turn essential for soil fertility. To this end, Agroscope has developed a software program for farms (Humus Balance Calculator) for testing the organic-matter content of the soil and adjusting it through practices such as appropriate crop rotation, the application of organic manure, and intercropping.

Fertility and cultivation systems

A research project conducted at an international level over a 10-year period compared various field cropping systems – conventional farming with and without ploughing, organic farming with ploughing, or no-till – in terms of yields and environmental impacts. Numerous parameters such as productivity, nutrient balance, microbial diversity, susceptibility to erosion and carbon sequestration have already been investigated.

Initial results after four years show that the no-plough methods and organic farming have a positive impact on soil functions and energy balance.

Despite these significant environmental benefits, however, yields are decreasing from one year to the next. Agroscope researchers are therefore currently examining which agricultural practices combine high yields with environmental benefits. They are also testing the potential of soil microorganisms to reduce fertiliser applications.

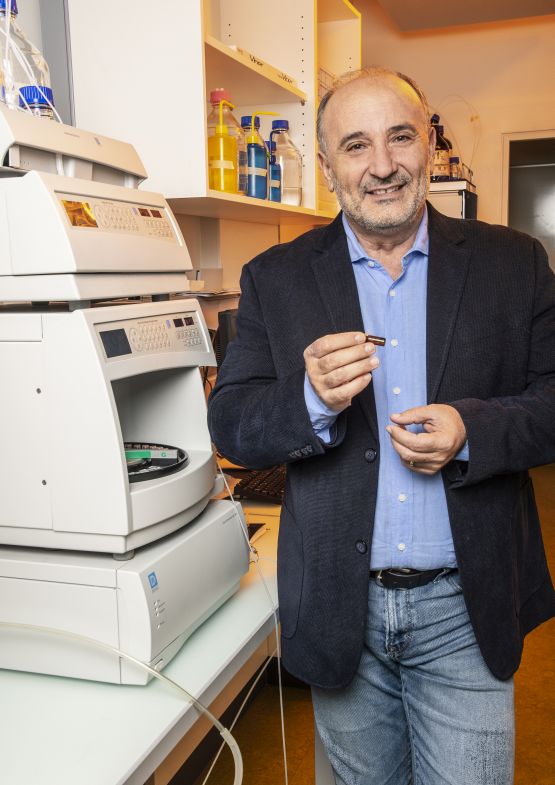

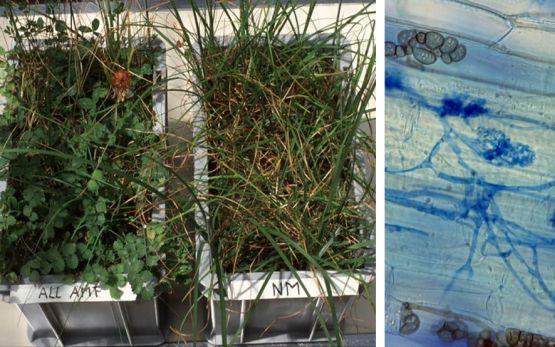

The potential of the soil microbiome

Microorganisms in the soil play a key role in soil fertility and plant growth. To give just two examples, bacteria living in symbiosis with clover absorb significant amounts of nitrogen, and mycorrhizal fungi (which form symbiotic associations with plant roots) make considerable amounts of phosphorus and trace elements available to plants.

The aim of Agroscope’s research is to better understand these biological soil processes, and to identify useful bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere microbiome. Laboratory experiments with model systems show that an increase in microbial diversity and in the number of soil-dwelling organisms promotes the absorption of nutrients by plants and reduces leaching losses. Trials with mycorrhizal fungi are currently being conducted on several maize plots with the aim of increasing soil fertility. On some fields, 30% higher yields were observed after inoculation with the fungus; on others, no impact was noted. In another project, commercially available products containing microorganisms beneficial for the soil were tested. It emerged that the quality of these commercial products varied greatly, and that up to 50% of the microorganisms contained in these products were incapable of survival.

These results lead us to the conclusion that the products are of unsatisfactory quality, and that a quality assurance system should be introduced.

These examples of current soil research illustrate how Agroscope is working to find answers to concrete problems on fertility, efficient use of resources, compaction, and the improvement of the soil in its function as a sustainable basis of life. Long-term trials are a particularly valuable tool for better understanding, modelling and testing the impacts of different agricultural practices. In future, research projects will continue to aim to provide practical solutions that will safeguard the sustainable fertility of agricultural soils.