From Control Station to National Centre for Agroecology: History of the Agricultural Research Institute Zurich-Reckenholz 1878-2003.

Kontakt

- Founding of the First Swiss Federal Control Station

- The Period at the Zurich Polytechnic (1878-1914)

- Expansion of Experimental Activity (1919-1938)

- Founding of the Swiss Grassland Society (AGFF) (1934)

- Under the Banner of the Wahlen Plan (1939-1945)

- Technological Innovation (1946-1960)

- A Period of Radical Change (1961-1996)

- Focus on Plant Breeding, Agroecology and the Environment (1996 onwards)

Founding of the First Swiss Federal Control Station

With the new Federal Constitution of 1848, a modern welfare state slowly developed in Switzerland. Gradually, the realisation dawned that the federal government would have to provide increasing financial support for teaching institutions and experimental stations. In 1853, the canton of Zurich opened its Arable Farming School in Stickhof (Zurich), whilst the canton of Bern followed suit in 1860 at Rütti (Zollikofen). A cantonal chemical control station was affiliated with the Rütti school in 1865. The opening in 1871 of the Agriculture department at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich – the present-day Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich (ETHZ) – marked a milestone in the development of agricultural education and experimental research.

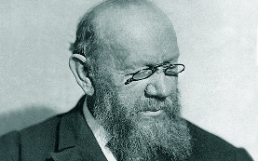

The first Swiss federal control station was established in January 1878 on the initiative of Friedrich Gottlieb Stebler (1842-1935) as a response to the shortcomings prevailing in the agricultural inputs trade. Stebler had set up a private seed control station in Bern back in 1875. In its issue of 2 February 1878, the Bernische Blätter für Landwirthschaft, a local agricultural newspaper, reported that “[the] Federal resolution [of] 17 March 1877 has created an agency for agricultural research in the Agriculture and Forestry Department of the Swiss Federal Polytechnic. Conducted under the supervision of the Swiss School Council, the organisation of this new institute, which comprises a seed control station and an agrochemical testing station, has now concluded. The seed control station has already commenced its work (1 January 1878); the agrochemical station will be opened on 15 March.”

The Period at the Zurich Polytechnic (1878-1914)

Stebler was appointed the first Head of the Schweizerische Samenuntersuchungs- und Versuchsanstalt (=’Swiss Seed Research and Experimental Institute’), whilst Ernst August Grete (1848-1919) headed the Schweizerische agrikulturchemische Untersuchungsanstalt (=’Swiss Agrochemical Research Institute’). Initially, both research stations were subordinate to the Swiss School Council. In 1898 they were detached from the Polytechnic and placed under the authority of the Swiss Federal Department of Agriculture as independent institutes. For the first few years, both institutes were housed in the attic of the Agriculture Department of the ETH Zurich. In 1886, they moved into the right wing of the newly constructed Chemistry Building.

To begin with, the heads of both institutes handled their respective workloads as virtual one-man operations, but staff numbers soon grew. In particular, the Seed Control Station, skilfully and successfully run for 42 years by its founder, Stebler, developed into an institute with a worldwide reputation. Stebler’s seminal works on forage production garnered him recognition and esteem far beyond the borders of Switzerland.

In numerous presentations and courses, Stebler and Grete encouraged farmers to purchase agricultural inputs jointly. In this way, not only were cost savings achieved, but also – thanks to the inspection process – the purchase of goods of impeccable quality was guaranteed. Thus, Swiss agricultural control stations made an essential contribution to the establishment of the agricultural cooperatives.

Taken by Surprise by the First World War (1914-1918)

The Swiss Confederation had purchased a plot of land on Birchstrasse in Zurich-Oerlikon In 1908, with the aim of establishing a new experimental field for the two stations. The long-awaited new building was erected on part of this site between 1912-14, and was ready for occupation at the end of May 1914.

The outbreak of the First World War on 1 August 1914 caught Switzerland completely unprepared. What’s more, inadequate domestic food production made the situation even worse. At this time, Switzerland was importing 85 per cent of its grain requirement. Although the Schweizerische Samenuntersuchungs- und Versuchsanstalt in Lausanne had begun initial breeding work back in 1899, efforts to encourage grain cultivation were only just beginning. At the behest of the Department of Agriculture, therefore, breeding work on landraces was also initiated in Zurich-Oerlikon.

At the same time that cereal breeding was being organised, however, the foundations for seed production needed to be laid. Initially, individual ‘seed breeders’ were trained in the multiplication of seed; later, breeding associations were created. These associations eventually led to the establishment of seed-breeding cooperatives. The first trials with potato and fodder-beet varieties were set up shortly before and during World War I.

Expansion of Experimental Activity (1919-1938)

On 1 January 1920, the Lausanne and Zurich-Oerlikon institutes were combined into the Swiss Federal Agricultural Experimental Station Zurich-Oerlikon. In the years that followed, the inspection of agricultural inputs absorbed the lion’s share of the workforce and funds. Impetus was given to the development of new, more efficient control measures with the aim of coping with the flood of new inputs and the growing problems of the sector.

At the time, potato varieties were in a huge muddle. In partnership with the Association of Swiss Experimental Stations and Distributive Agencies for Seed Potatoes (VSVVS; founded in 1925) potato-growing trials were conducted that enabled the varieties to be ‘straightened out’. It was at this time that the significance of viral diseases for potato cultivation was first recognised, and the production of seed potatoes launched as a response.

Whilst cereal cultivation initially created “refined landraces”, the aim now was to improve specific traits of these breeds. An attempt was made to enrich the genotype of native varieties via crossing with foreign varieties, thereby achieving better standing ability and a higher yield; later, breeding for good baking quality also gained in importance. The systematic variety-testing of maize began with high hopes. Maize breeding was commenced inter alia according to the ‘inbreeding and crossing’ method.

The increase in arable farming was also associated with problems, leading to the emergence of new plant diseases, previously almost-unknown pests, and new weed problems. Plant protection developed into a separate, very important ancillary discipline of agriculture.

An important focus of these years was the search for new methods for determining the quantity of plant-available nutrients in the soil, in order to improve the basis for advice on fertiliser application. To this end, a simple convertible greenhouse for container-growing trials and a lysimeter facility were erected near the Zurich-Oerlikon Experimental Station in 1922.

Founding of the Swiss Grassland Society (AGFF) (1934)

The AGFF was founded in 1934 in Bern, based on an idea advocated by Friedrich T. Wahlen. The aim was for all groups with an interest in forage production to join the new organisation, so that solutions to quality problems could be worked out in close cooperation with the agricultural schools and research institutions, and implemented in practice. The inventory from 1921 to 2009 documents the extensive trials and research projects conducted in the sphere of forage production, and the efforts made towards knowledge transfer via the bulletins, forage-production booklets, pamphlets and off-prints published by the AGFF. The systematic cooperation between science and agricultural practice that is characteristic of agricultural development is superbly documented.

The inventory can be downloaded as a pdf here, and is also contained in the "Quellen zur Agrargeschichte" (= "Records of Rural History") database of the "Archives of Rural History", www.agrararchiv.ch.

The documents are housed on Agroscope’s Reckenholz site, and may be consulted by arrangement with the Managing Director of the German-speaking Swiss section of the AGFF, Dr. W. Kessler.

Under the Banner of the Wahlen Plan (1939-1945)

In an effort to learn from past mistakes, there was a rapid reaction to the worsening political situation in 1930s Europe. Precautionary wartime measures were initiated in good time. Friedrich Traugott Wahlen, Head of the Zurich-Oerlikon Experimental Station since 1929, took over the reins of the ‘Agricultural Production and Household Management’ section of the Swiss Federal War Food Board. As the driving force behind the Anbauschlacht or Anbauwerk – the programme for increasing Swiss wartime food production – from 1940 to 1945, Wahlen achieved an almost unprecedented popularity with the Swiss public.

With the outbreak of the war, the Zurich-Oerlikon Experimental Station placed itself chiefly at the service of the Anbauwerk (usually referred to as the ‘Wahlen Plan’ in English). In the ‘Report on the Activity of the Swiss Federal Agricultural Research Station Zurich-Oerlikon from 1938 to 1942’, Wahlen praises the research station’s role in the historically noteworthy Anbauwerk: “The reporter would also like to take this opportunity to thank his staff for the numerous suggestions and the assistance that stood him in good stead in the organisation and implementation of the Anbauwerk, and which to a large extent helped to ensure the latter’s success.”

Technological Innovation (1946-1960)

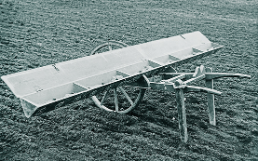

In the post-war years, few decision-makers in the agricultural sector doubted the magnificence and efficiency of the technical achievements that characterised this era. The Anbauschlacht or Wahlen Plan had lasting consequences for Swiss agricultural policy. In the shadow of the Cold War shaping the political situation in Europe, Switzerland continued to strive for an appropriate degree of self-sufficiency, aiming to devote at least 300,000 hectares to field crops.

Agricultural-input inspection tasks and informational and advisory activity – mainly on fertiliser-application and plant-protection issues – continued to lay claim to a sizeable chunk of the human and monetary resources and facilities of the research stations. From 1953, Zurich-Oerlikon began publishing its own in-house agricultural journal, Mitteilungen für die Schweizerische Landwirtschaft.

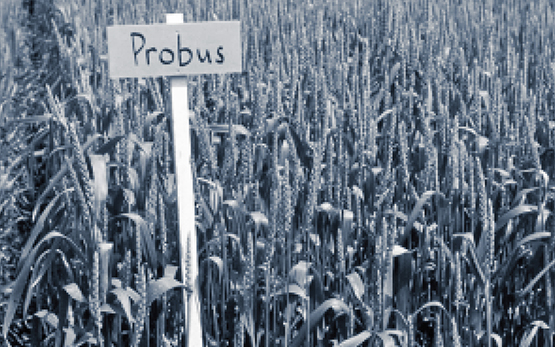

In the sphere of potato production, the main focus was on producing healthy seed potatoes. The Zürich-Oerlikon and Lausanne research stations made their first major breakthrough in cereal breeding with ‘Probus’, a winter-wheat cultivar. The first domestic maize hybrid in the Swiss standard range, ‘ORLA 266’, was adopted in 1955. In the same year, breeding work began with forage plants, and the ‘Standard Mixtures for Forage Production’ was published for the first time.

A Period of Radical Change (1961-1996)

In the 1960s, there was growing recognition that further increases in productivity, higher incomes and improved competitiveness in the agricultural sector were dependent on scientific foundations provided by research and development work. To this end, a total of CHF 268 million was invested in the expansion of the agricultural research stations between 1963 and 1975. At the same time, the experimental stations were renamed "research stations".

Planning commenced in 1959 for new buildings on the grounds of the Reckenholz estate on the northern border of Zurich-Affoltern, land which the Swiss Confederation had acquired in 1943. The new buildings were eventually occupied in 1968-69. Research activity was further expanded thanks to a considerable increase in staff numbers. Electronic data processing was introduced in several stages. The purchase of two farms in Ellighausen (canton of Thurgau) in 1970 and 1972 allowed the establishment of 37 hectares of new experimental land. A further 30 hectares in Oensingen (canton of Solothurn) have been leased on a long-term basis since 1983.

Research increasingly focused on developing environmentally friendly production methods and improving the quality of the harvested crop. Quality seed and planting material for cereals, maize, potatoes, other field crops and forage plants was heavily promoted. New native and foreign varieties were tested under Swiss growing conditions, and successful ones were published in the appropriate variety lists. An experimental network set up in conjunction with the Changins Research Station with the assistance of the Schweizerischer Saatzuchtverband (=Swiss Seed-Breeders Association) also supported this work. A large number of in-some-cases very successful new varieties of winter and summer wheat, spelt, maize, clover and grass species bear witness to the efficient breeding work conducted over these decades. Since the 1990s, bioengineering methods such as molecular markers have also been used.

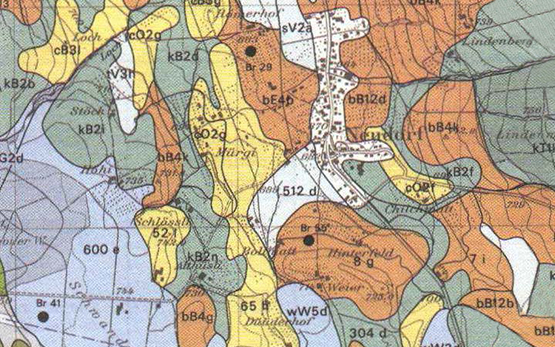

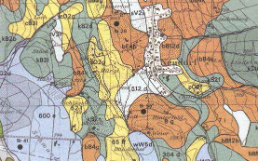

In addition to chemical control approaches, biological approaches to plant protection became increasingly important. Terms such as “critical infestation rate” and “economic damage threshold” became key concepts. The new plant-protection ordinances required the biological testing of compounds and regulated the expansion of warning and alert services. The ‘Guidelines for Fertiliser Application in Arable and Forage Crops’ (GRUDAF) facilitated the provision of advice on fertiliser application, as did soil maps published by the Soil-Mapping Service. Produced to a scale of 1:25,000, these maps contain notes regarding suitability for cultivation, irrigation requirements, and soil resilience to liquid fertilisers. In connection with the expansion of the agricultural research stations, a ‘forage production’ group was created in the 1960s to deal with issues of natural and ley pasture farming.

Focus on Plant Breeding, Agroecology and the Environment (1996 onwards)

Since the mid-1980s, reduced funding has generally led to staff cutbacks and noticeable reductions in service provision. Further decisions to cut spending made a reorganisation of agricultural research unavoidable. As part of this reorganisation, the Swiss Federal Research Station for Agroecology and Agriculture (FAL) was created in 1996 as the national centre for agroecology from the merger of the former Federal Research Station for Agricultural Plant Development in Zurich-Reckenholz (FAP) and the Federal Research Station for Agricultural Chemistry and Environmental Hygiene in Liebefeld-Bern (FAC). The research farm in Liebefeld was run as the Institute of Environmental Protection and Agriculture (IUL), then relocated to Reckenholz on 1 January 2000, where it was dissolved as an organisational unit. For the employees of both research stations, the new reorganisation meant an in-some-cases painful leavetaking from their place of work (in the case of the IUL) or from activities in which both research stations had earned themselves a name both in Switzerland and abroad over many decades.

Because intensive use of the soil was characteristic of agricultural practice at this time, the notion of soil conservation advocated in research conducted at the new institute in Zurich-Reckenholz gained in significance. The change of name of the two merged institutes to ‘Swiss Federal Research Station for Agroecology and Agriculture’ stressed the importance of the ecological aspect. The FAL’s motto, “Research for agriculture and nature”, underscored how the protection and sustainable use of natural resources formed a unit, and were of key importance for the research station’s work.

Mit der intensiven Nutzung des Bodens gewann der Schutzgedanke in der FAL-Forschung an Bedeutung. Der Namenswechsel zur "Forschungsanstalt für Agrarökologie und Landbau" macht die Gewichtung der ökologischen Aspekte deutlich. Das Motto "Forschung für Landwirtschaft und Natur" bringt zum Ausdruck, dass das Schützen und schonende Nutzen der natürlichen Ressourcen eine Einheit bilden und für die Arbeit von zentraler Bedeutung sind.

On 1 January 2014, all of the research stations were merged under the name Agroscope. Agroscope became the Swiss federal centre of excellence for research in the agriculture and food sector, organised into four institutes under the direction of the Head of Agroscope (CEO). Agroscope Council – a body tasked with defining strategic orientation – was also set up.

The reform continued in 2016 with the simplification of Agroscope’s structure. On 1 January 2017, the four institutes and 19 research divisions were abolished. Agroscope’s research services and enforcement tasks are now the responsibility of 10 newly created units – three competence divisions for research technology and knowledge exchange, and seven strategic research divisions. This brings operational management and staff closer together, with the aim of fulfilling the research organisation’s key tasks for the agriculture and food sector with greater efficiency and flexibility, and defining a clear service portfolio.

Reckenholz became the main "Agroscope East" site, with two of the ten new units – the "Plant Breeding" and "Agroecology and Environment" research divisions – headquartered there.