In the perishable goods hall of an airport, the waiting time for inspection must be short. But when suspicious organisms are found in the freight, they must be identified in order to keep quarantine organisms out of Switzerland. Thanks to a method optimised for use in practice, this now takes just two hours instead of two days.

“Time is money” – this quotation from Benjamin Franklin, the American inventor and statesman, is particularly true in the perishable goods hall of an airport. There, newly arrived goods from the four corners of the earth pile up – fruit, vegetables, cut flowers and much more.

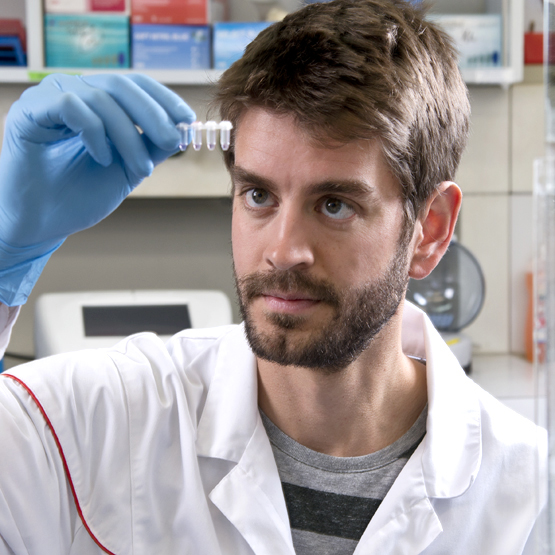

One person who tests these goods at Zurich airport for pathogens is Hanspeter Diem, a plant-protection inspector at the Swiss Federal Plant Protection Service SPPS. In a suspected case, he must determine whether quarantine organisms are present. These organisms must be stopped at Customs, as the majority of them are not yet present in Switzerland, and could cause major damage in the agricultural, horticultural or forestry sector.

Often, however, Diem finds only insect eggs or larval stages that cannot be unequivocally identified by eye. Such samples must be genetically analysed, and are sent to Agroscope’s central laboratory. “Previously, we waited two days for an answer” explained Diem. Although two days is good from the laboratory perspective, space in the airport hall is limited; what’s more, perishable goods can’t afford to be kept waiting. Hence, the need for a quicker method.

2011 – First flight attempts

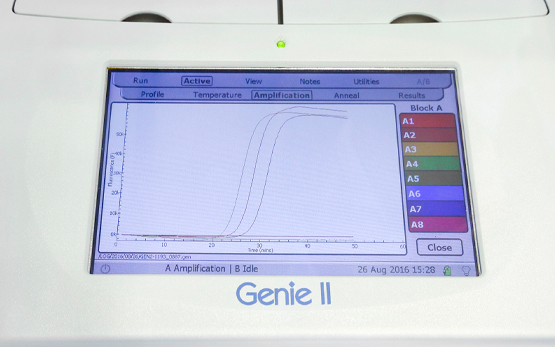

It was with just such a method that Andreas Bühlmann travelled to the airport in 2011. A PhD student, he was researching a quick method for identifying harmful organisms by means of a genetic fingerprint – similar to a paternity test. During filming of the programme ‘Einstein’ for Swiss television, he gave an on-the-spot demonstration of the LAMP (=loop-mediated isothermal amplification) method – a process for chemically amplifying DNA at a constant temperature.

If the plant-protection inspector discovers a suspicious insect, he places two of the creatures in two separate test-tubes with an extraction solution. The solution is heated, releasing the DNA. Two control test-tubes, each containing one specimen of the quarantine organism in question, also form part of the testing kit. The four tubes are inserted in a detection device that is smaller than a shoe box. There, the sample is heated to 65 degrees Celsius. At this temperature, a DNA polymerase makes copies of specific sections of the genome.

After no more than two hours, the results are visible: if DNA sections were amplified which only match the control quarantine organism, the results are positive, and the tested insect is indeed a quarantine organism.

2015 – Clearance for take-off

In 2011, i.e. still in the same year, the method was presented at an Inspectors’ Workshop of the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization EPPO in Padua, Italy. One of the participants was Andreas von Felten, Diem’s boss and the person responsible for plant-protection inspections in Switzerland. With London Heathrow also poised to launch such a system, von Felten realised at once that Bühlmann’s method had a future.

Andreas von Felten got in touch with Jürg Frey, Bühlmann’s supervisor at Agroscope. Von Felten and Frey agreed that the innovation potential was there, but the method’s successful implementation in practice was critically dependent on the training of the people who would be working with it. This task was assumed now by Simon Blaser, after Andreas Bühlmann had finished his PhD.

For Blaser, introducing the LAMP method at the airport meant on-the-spot training of specialist staff, and overcoming problems. He introduced an extraction method even simpler than the original one, and added dye to all of the reagents to make them clearly visible, thereby reducing the risk of mistakes. Blaser succeeded in his task.

2016 – Optimum altitude reached

From 2015 to 2016, 59 samples were tested both at the airport and in the Agroscope laboratory. All results detecting a quarantine pest were positive both on-site and in the lab. Thanks to the quick decision, the importer would now still have time to organise a replacement delivery.

However, around two per cent of the negative test results were false negatives. This means that in two out of every hundred imports, a quarantine pest would have entered the country undetected. That’s why to this day, negative results are still examined in the Agroscope laboratory, and the relevant testing kits are being refined. Agroscope now provides kits for identifying several fruit flies of the genus Bactrocera, as well as for Thrips palmi, Bemisia tabaci and three Liriomyza species (L. sativae, L. trifolii and L. huidobrensis). Hanspeter Diem would like to see testing kits for additional insects, as well as for fungal diseases on citrus fruits.

Smooth cruising to the next destination

Jürg Frey, the actual father of the use of this method, has been identifying agriculturally important organisms by means of genetic barcodes since 1995 – because, provided that it is solidly validated, genetic identification is quicker and more reliable than classic morphological identification.

Frey worked on LAMP methods inter alia as part of the EU projects QBOL and Q-Detect, after which he continued to refine the LAMP system described above. By now, the system used at Zurich airport is the most advanced in the world.

But Frey is already working on the next step: “The future belongs to sequence-based diagnostics. With LAMP, you see, we can only tell whether the sample is type A or not.” In other words, each quarantine organism needs a validated test of its own. “The aim is actually a system that tells us which species the sample belongs to” says Frey, placing a little box on the table – a nanopore sequencing device the size of a large pocket knife. “The problem is still the preparation of the sample – the process is too complicated, but we’ll solve that too…”