When young pigs from different breeding facilities are brought together on a fattening farm, they often require treatment for infectious diseases. If antibiotics are administered via a pipeline system in liquid-feed units, the bacteria in the pipes can become resistant and wind up in the pigs’ stomachs through the feed. But just how serious is the situation?

To prevent chronic diseases and mortality, whole groups of pigs are often treated on fattening farms. On farms where the feed is piped into feed troughs in liquid form as ‘feed soup’ via a pipeline system, antibiotics are often mixed into the soup while it is still in the feed-mixing container. They are then conveyed to the animals via the pipelines. A highly stable biofilm composed of bacteria adheres to the walls of these pipes. If these bacteria come into contact with the antibiotics in the feed soup, there is a risk of them becoming antibiotic-resistant. Particles detaching from the pipe walls carry these resistant bacteria into the feed, and are conveyed with the feed into the pig’s gut, where they can pass on their resistance genes to intestinal bacteria.

Enterobacteriaceae testing on 27 farms

To quantify this risk, we investigated the current situation in terms of the antibiotic-resistance of bacteria in liquid-feed units as part of the Agroscope Project REDYMO (‘Reduction and Dynamics of Antibiotic-Resistant and Persistent Microorganisms’). In partnership with the Department of Porcine Medicine and the Institute for Food Safety and Hygiene, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Zurich, 13 pig-fattening farms which regularly administered antibiotics via pipelines were studied and compared with 14 farms which had not administered any antibiotics in this manner for at least two years. Over the course of a fattening cycle, a doctoral student took several liquid-feed samples on all of the farms. The Enterobacteriaceae levels of these samples were determined in the laboratory via culturing on a nutrient medium without the addition of antibiotics. In addition, the number of Enterobacteriaceae resistant to the antibiotic tetracycline and the antibiotic combination of sulphonamide+trimethoprim was determined for each sample. This was done via culturing on nutrient media containing these antibiotics.

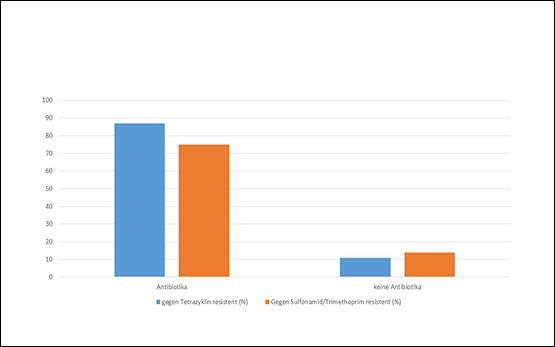

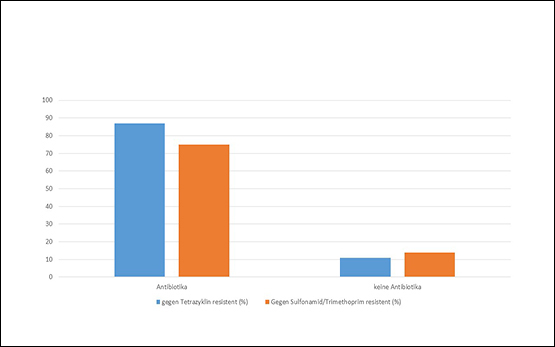

Antibiotic resistance in over 80% of samples

Over 80% of the liquid-feed samples from the farms administering antibiotics via the pipeline system of the liquid-feed units contained tetracycline-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Moreover, two-thirds of the samples contained Enterobacteriaceae resistant to the combination of sulphonamide + trimethoprim (see graphic). On farms where no antibiotics were administered, the percentage of samples with resistant Enterobacteriaceae was fewer than 15%.

A different way to administer antibiotics

The percentage of resistant bacteria in the biofilm colonising the pipelines of a liquid-feed unit increases massively on contact with antibiotics. Eliminating existing biofilms in the pipelines is all but impossible. This means that resistant bacteria in pipelines can probably survive for extended periods, contaminating the feed and colonising the animals, even when the farm has in the meantime stopped administering antibiotics via the liquid-feed unit. In order not to exacerbate the antibiotic resistance of animal bacteria, and indirectly that of bacteria living on humans, the administering of antibiotics via liquid-feed units must be strongly discouraged. If blanket treatment is necessary, the antibiotic must be mixed directly into the feed in the feed troughs.